NOVA Chamber Music Series

Fry Street Quartet, music directors

Fry Street Quartet, music directors

Sonata in A minor, Wq. 49/1, H. 30 “Württemberg”

C.P.E. Bach

(1714-1788)

Viktor Valkov piano

I. Moderato

II. Andante

III. Allegro assai

Carl Philipp Emmanuel (C.P.E.) Bach was the fifth of J.S. Bach’s twenty children and his second surviving son. As a composer, C.P.E. Bach served as a bridge between the Baroque mastery of his father and the formal Classicists who followed. Mozart apparently held him in very high regard, as did Haydn, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Weber. But Schumann did not. C.P.E. Bach’s music fell out of favor in the 19th century, and Schumann’s opinion that he couldn’t hold a candle to his father probably helped that somewhat natural process along. But with the 300th birthday celebrations that happened across Germany in 2014, C.P.E. Bach once again claimed a rightful place in our minds and our history books, even if performances of his works are still quite rare. C.P.E. Bach wrote over 150 keyboard sonatas during his productive life, six of which were composed in the mid-1740s and dedicated to his pupil, The Duke of Württemburg. The challenging “Württemburg” Sonatas allow us a glimpse into the personal style and abilities of, not the Duke per se, but C.P.E. himself. They are experimental, intellectually curious, and heartfelt. Rising in German music at the time, and championed by Bach fils, was the concept of “Empfindsamkeit” (sensitivity), which promoted emotion as an equal to technique when communicating with an audience.

Violin Sonata No. 2, Sz. 76

Béla Bartók

(1881-1945)

Rebecca McFaul violin | Mayumi Matzen piano

I. Molto moderato

II. Allegretto

Rarely just one thing or another, Béla Bartók’s compositions typically stood at intersections — of academia and folklore, of Europe and Hungary, of the various “schools” of artistic thought that laid claim to the new 20th century. He was a good student, a diligent observer of the prevailing creative winds that shaped his environment. And then he became one. One of the concepts Bartók explored and then immediately assimilated into his own peerless voice was the “expressionism” of Schoenberg and others. Bartók was never one to embrace absolute abstraction and, as a perfect example, his brief dalliance with the twelve-tone technique was highly individual but never completely atonal. The two violin sonatas Bartók wrote in 1921 and 1922 are from this interesting period of consideration and experimentation. Violin Sonata No. 2, Sz. 76 differs formally from No. 1 by employing a connected, two-movement structure but, exactly like the earlier piece, No. 2 is highly demanding and can’t help but default to some wonderfully impetuous dance music (of a sort) for the finale. It’s not based on a folk tune, at least not literally, but the second movement clearly reflects Bartók’s fascination with the improvisatory song traditions of the Hungarian villages. Even at his most “modern”, he was fully himself.

Parallel Play

Miguel Chuaqui

(b. 1964)

Zachary Hammond oboe | Erin Svoboda-Scott clarinet

Lori Wike bassoon | Michael Sammons percussion

This piece was commissioned by the NOVA Chamber Music Series.

Utah-based composer Miguel Chuaqui is fascinated with the process of translation. “Often,” he recently told me, “I’m frustrated that a single language can’t capture all the nuances I try to express in my speech and in my writing.” Chuaqui’s new work Parallel Play, which has its world premiere on today’s program, deals directly with this question and what he calls “the complexities of my background in music.” According to his program note, Chuaqui “was born in California to a Chilean father and an Andean mother, grew up bilingual in Santiago, and have lived in the United States for decades.” He goes on to say that he “can claim musical influences from both the U.S. and Chile, but I often find myself expected to become an American composer in Chile and a Chilean composer in the U.S.” Parallel Play attempts to embrace this bivalence by frequently casting the clarinet as the “American” voice and the oboe as the “Chilean”. The bassoon, in Chuaqui’s words, acts a “somewhat ironic observer” while the percussion instruments reflect flexibility on everything around them without any particular allegiance. “As the piece progresses,” Chuaqui’s note continues, the players “tend to develop their motives in parallel…as if they were playing with different toys but in the same ‘room’.”

a note from the composer:

Parallel Play is a work in which I play with the complexities of my background. I was born in California to a Chilean father and an American mother, grew up bilingual in Santiago, and have lived in the United States for decades. I hold dual citizenship and I can claim musical influences from both the U.S. and Chile, but I often find myself expected to become an American composer in Chile and a Chilean composer in the U.S.

In many of my works I disregard this issue, but this piece plays with these expectations from the beginning by presenting a chromatic gesture marked bluesy in the clarinet followed in the oboe by what I hear as a typical Chilean folk-music gesture: a quick leap to a high note preceded by two quick short notes, marked cantando (singing) in the score. These two gestures are juxtaposed, superimposed, combined and developed in different contexts throughout the piece, and they are connected often to the clarinet and the oboe. The bassoon tends to be a somewhat ironic observer, interrupting the opening sustained phrase of the piece (which includes the bluesy music and the cantando music) with a version of the cantando leap that is, however, short and abrupt (with grace notes and silences, which the oboe and clarinet take up immediately). The percussion shares characteristics of each of the other instruments, with passages that are jazzy or ironic, or that are typical of Latin American music (such as off-beat accents in 6/8 time, typical of folk music from central Chile).

As the piece progresses, the instruments tend to develop their motives in parallel, rather independently, but still influencing each other, as if they were playing with different toys but in the same “room.” However, they come together frequently to develop another strand of music in the piece: descending harmonic progressions in parallel motion based on fifths (marked dolente – sorrowfully), which become more intense toward the end of the piece.

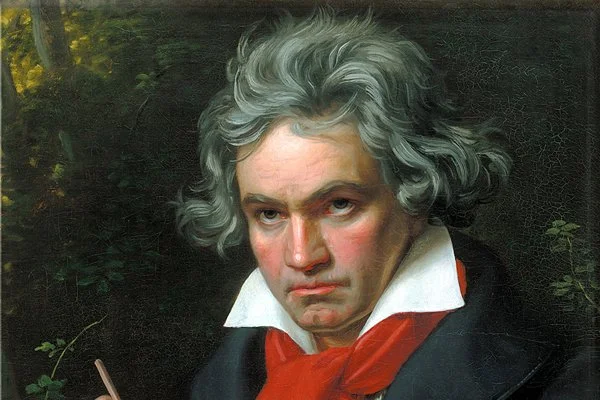

Piano Trio in D major, op. 70 no. 1 “Ghost”

Ludwig van Beethoven

(1770-1827)

Alex Woods violin | Andrew Larson cello

Viktor Valkov piano

I. Allegro vivace e con brio

II. Largo assai ed espressivo

III. Presto

The only composer subjected to more nickname abuse than Beethoven was, of course, Papa Haydn. The catalogues of both men are filled with clever unrequested monikers, bestowed by others out of either enthusiasm (critics) or ambition (publishers). Beethoven did choose “Pastoral” and “Eroica” himself, but “Moonlight”? Nope. “Emperor”? Definitely not; he would have hated that one. Who knows, then, how he would have felt about “Ghost”, the alias for the Piano Trio in D minor, op. 70 no. 1? Beethoven’s student Carl Czerny is often credited, but regardless of who said it first, the name is now written in stone. The “ghost” perceived by Czerny and others presents itself in the second movement. The largo is the brooding, eerie centerpiece of the trio and, by all accounts, proof that Beethoven was working towards an opera based on Shakespeare’s Macbeth. This speculation arises from the fact that, written very near a sketch for the spectral slow movement in his notebooks was the word “Macbett”. It’s tantalizing to imagine this music as meant for the stage and it certainly seems purpose-built to underpin a supernatural plot point from an opera about a murderous Scottish king. But ultimately, we are just guessing. Hence, the nickname and its restless, purgatorial connotations.

NOVA would like to recognize the following government, corporate, and foundation partners for their generous support of our mission:

Aaron Copland Fund for Music

Cultural Vision Fund

Marriner S. Eccles Foundation

O.C. Tanner

Rocky Mountain Power Foundation

Sorenson Legacy Foundation

Utah Legislature | Utah Division of Arts & Museums

Utah State University Caine College of the Arts Production Services

In-kind contributors include:

AlphaGraphics

Bement & Company, P.C.

Michael Carnes

Taylor Audio

University of Utah School of Music

Utah Museum of Fine Arts

Utah State University Caine College of the Arts Production Services

Michael & Fran Carnes

John & Linda Francis

Eric & Nancy Garen

Joan & Francis Hanson

Hugh & Cindy Redd

Richard Segal

Kathryn Waddell

Frank & Janell Weinstock

Miguel Chuaqui in memory of Andrew Imbrie

Hillary Hahn & Jeff Counts

Diane & Michael L. Hardink

Keith & Suzanne Holbrook

Gordon Irving

G. Ronald Kastner, Ph. D.

William & Pam Littig

Douglas & Julie Meredith

Dr. Glenn D. Prestwich & Rhea Bouman

Aden Ross & Ric Collier

Steven & Barbara Schamel

Richard & Jill Sheinberg

Shiebler Family Foundation

Paul Watkins in memory of Beverly Watkins

Gail & Ned Weinshenker

Rachel White

Madeline Adkins & John Forrest

Alan & Carol Agle

Doyle L. Arnold & Anne T. Glarner

Sally Brush

Gretchen Dietrich & Monty Paret

Mark Gavre & Gudrun Mirin

David & Sherrie Gee

Josanne Glass & Patrick Casey

Ann & Dean Hanniball

Fred & Annette Keller in honor of Eric & Nancy Garen

Rendell Mabey

Jeffrey & Kristin Rector

Hal & Kathleen Robins

Susan and Glenn Rothman

Michael Rudick & Lani Poulson

Catherine Stoneman

Richard & Anna Taylor

Lila Abersold

Suzanne & Clisto Beaty

Larry & Judy Brownstein

Anne & Ashby Decker

Denise Cheung & Brad Ottesen

Andrea Globokar

Janet Ellison

Darrell Hensleigh & Carole Wood

Joung-ja Kawashima

Kimi Kawashima & Jason Hardink

Dr. Louis A. & Deborah Moench

Lynne & Edwin Rutan

Barry Weller

Brent & Susan Westergard

Kristine Widner in memory of David Widner

Susan Wieck

Carolyn Abravanel

Frederick R. Adler & Anne Collopy

David & Maun Alston

Marlene Barnett

Klaus Bielefeldt

Dagmar & Robert Becker

Linda Bevins in memory of Earle R. Bevins and Yenta Kaufman

Fritz Bech

Kagan Breitenbach & Jace King

Mark & Carla Cantor

Dana Carroll

David Dean

Disa Gambera & Tom Stillinger

Cherie Hale

Scott Hansen

Thomas & Christiane Huckin

Cheryl Hunter in honor of Leona Bradfield Hunter

James Janney

Karen Lindau

Gerald Lazar

Margaret Lewis

William & Ruth Ohlsen

Karen Ott

Marge & Art Pett in memory of Classical Music on KUER

Mark Polson

Daniel & Thelma Rich

Becky Roberts

Steve Roens & Cheryl Hart

John & Margaret Schaefer

John Schulze

Kimberly & Spence Terry

Jonathan Turkanis

David Budd

Cathey J Tully

Elizabeth Craft

Paul Dalrymple

Amanda Diamond

Mila Gleason

Kristin Hodson

Sarah Holland

Kathryn Horvat

Kate Little & Ron Tharp

Kathleen Lundy

Ralph Matson

Jon Seger

Janine Sheldon

Robert & Cynthia Spigle

Michael Stahulak

Kody Wallace & Gary Donaldson

Steve Worcester

Anonymous (3)

Joan & Francis Hanson

Corbin Johnston & Noriko Kishi

G. Ronald Kastner, PhD

David Marsh

Steven & Barbara Schamel